|

OPMV IN AUSTRALIAN REPTILE COLLECTIONS. |

Raymond Hoser

488 Park Road

Park Orchards, Vic, 3114

Phone: (0412) 777 211

E-mail: adder@smuggled.com

(Editor's note: Since publication of this communication at end of June 2003, Electron Micrograph (EM) results have shown the virus to be a Reovirus. Notwithstanding this, all the factual account below remains the same and unchanged, the important point being that in terms of clinical and histological signs, both OPMV and reoviruses tend to present as the same. Published statements by John Weigel of the Australian Reptile Park (ARP) denying the possibility that a Taipan shipped by them in October 2002 was a potential carrier of virus have no factual basis or merit. Furthermore the ARP have since admitted fault for not notifying all recipients of their potentially infected snakes of the risk posed by them. This also means that the viral infection at the ARP in 2002 transmitted to Bigmore was probably the same Reovirus, not OPMV, although based on the size of their collection and lack of effective quarantine, OPMV is likely to have also been in the collection at the materially relevant time).

(Editor's note: Since publication of this communication at end of June 2003, Electron Micrograph (EM) results have shown the virus to be a Reovirus. Notwithstanding this, all the factual account below remains the same and unchanged, the important point being that in terms of clinical and histological signs, both OPMV and reoviruses tend to present as the same. Published statements by John Weigel of the Australian Reptile Park (ARP) denying the possibility that a Taipan shipped by them in October 2002 was a potential carrier of virus have no factual basis or merit. Furthermore the ARP have since admitted fault for not notifying all recipients of their potentially infected snakes of the risk posed by them. This also means that the viral infection at the ARP in 2002 transmitted to Bigmore was probably the same Reovirus, not OPMV, although based on the size of their collection and lack of effective quarantine, OPMV is likely to have also been in the collection at the materially relevant time).

(Second Editor's Note: Subsequent (end 2003) tests on the ARP's collection revealed two separate strains of OPMV (in addition to the reovirus previously detected) as being infecting their collection at the materially relevant time).

The following relates to a Ophidian Paramyxovirus (OPMV) outbreak at the facility of Raymond Hoser (myself) at the above address and over a dozen related cases.

In the period June 2003 (to 30 June), the date that this communication was written, four captive neonate death adders (Acanthophis spp.) of apparently good health developed various symptoms of neurological and respiratory disorders and died.

The last two of these snakes were actually observed dying in convulsions.

In summary, apparently healthy snakes declined sharply and within days would have convulsions and die. This decline usually came with respiratory ailment, typified by open mouth and some nasal discharge or even blocking.

All snakes (8 juveniles) were kept in separate and isolated cages adjacent to one another and in a room with about six other snakes of the same species (five adults, raised from hatchling the previous year, and a sixth adult as mentioned below) and a 1 metre Diamond Python and a 2 metre Carpet Python.

The husbandry of the snakes appeared sound in that these species have been kept in identical circumstance for several years without problem or ailment save for an unexpected mite plague that was successfully treated without casualty in mid 2002.

In terms of the snakes, the same trouble free past applied to such things as for other variable parameters such as food, substrate, temperature gradient in cages and the like.

Two further juvenile snakes in the same collection of the same age had shown symptoms of respiratory problem and recovered (bar a third one, which still has such symptoms). In those cases, the respiratory complaints lasted some weeks before recovery.

Noting that usual respiratory disorders arising from bacteria and the like stem from stress and caging disorders, such was not thought likely in these cases.

This possibility was further ruled out by the fact that separately housed and apparently healthy well-adjusted snakes developed the same disorder at more or less the same time.

There had been no alteration to the keeping parameters of these snakes.

Furthermore, the last of the snakes to die was witnessed in the terminal phase and had convulsions and the like and appeared to be breathing normally and nostrils unblocked, thereby effectively ruling out respiratory blockage as the cause of death.

All snakes to have died had exhibited the same sort of symptoms, commencing with neurological symptoms first (before respiratory) in the form of listlessness, unnatural postures loss of appetite and the like.

Those snakes that have exhibited symptoms and died all had neurological complaints before death and those that have apparently survived (and recovered) did not. The latter only had respiratory complaints.

All snakes have in the terminal phase been restless in the 48 hours before death, by moving around the cage constantly, which is not normal for the species.

All snakes to have been affected and died have been young (2003 born - Feb-Early May) Death Adders.

Adults of the same species in the same room and two pythons (both large) in the same room appear to be so far more-or-less unaffected (see below).

Several weeks ago (17-5-05 to 20-05-03), fourteen red-bellied black snakes were held in the same room as these snakes for four days only and at least six have since died of the same disorder (in the hands of another keeper) and within the last fortnight (to 30 June 2003).

These too were juvenile. Three other juveniles appear to remain outwardly healthy as do adults.

On 15 February 2003 two Adult death adders were received and housed in this room. Both were in exceptionally poor health and with numerous husbandry and parasite problems. One died and the other made an apparently full recovery.

In this process it had a respiratory complaint for about two months which eventually disappeared.

The snake that died also had respiratory infection.

In terms of the incoming Red-bellied Black snakes and the Death Adders, they were both (accurately) presumed to be carriers of OPMV and initially thought to be derived from unconnected infections.

That wasn't so (see later).

The original source of infection was also masked by some other factors, including the fact that the said snakes had been previously held at collections with contact with (legally held) non-native (exotic) reptiles, including Corn Snakes and Boas in terms of being housed in the same room and/or having been in the same room as other reptiles previously housed with the exotic reptiles.

As all snakes mentioned (at the Hoser facility) have been held individually (one per cage) in separate containers (plastic tubs as cages) with no direct contact at all possible between snakes, the means of transmission of the ailment was thought (erroneously) to be airborne.

This hypothesis remained some time after the diagnosis of OPMV because the literature generally indicates airborne means of infection. That is not so (see later).

Three large Death Adders had shown symptoms of respiratory disorder (evidenced via rubbing of exudate from their snouts), but so far their symptoms have not worsened. They may however decline over coming weeks or months and are being monitored closely and with great trepidation.

This evidence of the disorder was only noticed after one of the smaller snakes was noticed rubbing exudate from it's snout, leading to an investigation of the larger snakes.

The above facts (as related) initially presented problems in terms of identification of the source, but in the week following the death of the fourth snake on 22 June 2003, the picture did in fact become far clearer (see below).

The symptoms of these snakes also fits the profile of Ophidian paramyxovirus (OPMV), in particular the four phases of the symptoms as seen in these snakes, which fits the profile of OPMV.

(See details under "Clinical Signs:" from Elliott Jacobson's internet site at: http://www.vetmed.ufl.edu/sacs/wildlife/Pmyx.html).

The virus (or similar ones) is to date is little known in Australian collections.

To date only one officially reported case is known (at the Australian Reptile Park (ARP), Somersby, NSW, late last year involving a case and mass die off that ran from Feb-November that year).

This diagnosis was 'presumptive' based on clinical, gross and histological symptoms.

Other presumptive diagnoses have been made on four cases in Melbourne with the veterinary surgeon involved stating that he believed the disease is widespread and relatively undiagnosed due to the reluctance of reptile owners to pay for tests on already dead snakes.

Similar reports came from a Brisbane-based vet who specializes in reptiles.

There may also be several forms of OPMV in existence some or all of which may or may not be native to Australia (see below). Different forms of OPMV target different reptiles, often only one species in a collection, but in the Australian context the following trends are noted.

Death Adders (Acanthophis) and to a lesser extent other elapids appear most susceptible. This and these were the species most affected in the ARP die off. Small snakes in particular are vulnerable. Whilst evidence suggests that elapids are more susceptible to OPMV than pythons, veterinary surgeons who deal mainly in pythons tend to see evidence of it mostly in these snakes. That probably reflects the fact that elapids are mainly the province of 'experienced' keepers who will self-medicate common health problems or those that present as such.

The symptoms of OPMV are in many ways similar to the better-known IBD and several specialist reptile vets in Australia have suggested that most of the (small number of) provisional diagnoses of IBD in Australia are in fact OPMV.

The disease isn't known in wild reptiles and more-or-less unknown in collections sourced direct from the wild and no contact with other (captive) reptiles.

Thus the disease may be exotic to Australia, although this is by no means certain.

The virus may potentially pose a threat to local reptiles and hence should be diagnosed as soon as possible if it is in fact infecting captive reptiles.

All other relevant reptile holders have been notified of the recent deaths (above) and the likely cause.

The dead snakes have all been retained for Electron Microscope (EM) testing purposes as required and results of the first of these tests are anticipated shortly.

The preferred means of diagnosing OPMV is by Hemagglutination inhibition assay

This is a common diagnostic tool (the details of which are readily available via the internet).

Notable in the above account and also in terms of what is known about OPMV, is that the virus/es, do not necessarily affect all reptiles in a collection.

Some appear to either escape unscathed or are "asymptomatic carriers".

This means that persons with reptiles apparently unaffected by OPMV may in fact have carriers.

Asymptomatic carriers tend to be larger reptiles.

Quarantining of reptiles is therefore essential in all cases and especially when medium to large collections are involved.

Furthermore, notwithstanding the reference to snakes in OPMV, there is little doubt that this/these or similar viruses may affect captive lizards as well, even though as yet, little appears in the literature with regard to this, save for some recent cases reported from outside Australia.

The world's foremost expert on this virus is probably Dr. Elliott Jacobson from Florida.

His address is:

Box 100126

Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Florida

Gainesville, Florida 32610

E-Mail: JacobsonE@mail.vetmed.ufl.edu

Anecdotal evidence has suggested that OPMV and/or variants of it, may be more common in Australian collections that previously expected.

One collection, twice removed from my own (Hoser's) in terms of contact via snakes, also with legal exotics (Corn Snakes) has held two with a respiratory complaint. No other reptiles bar the adult Corn Snakes have shown symptoms and tests failed to identify the cause of the infection (bacterial cultures and the like).

The duration of this apparently uncurable infection has been 24 months. The symptoms while indicative of OPMV does not lead to a provisional diagnosis of OPMV on the basis of duration.

Generally OPMV affected snakes will either recover within four months or die. Symptoms that persist beyond this time frame are not generally known.

An unconnected South Australian collection had a significant die off of young Death Adders (Acanthophis sp.) from unknown causes and vet tests have so far failed to yield the cause. OPMV is suspected.

Reported mass die off's of Death Adders (Acanthophis spp.) in private collections in the late 1990's may have been OPMV related as no definite cause of death was ever diagnosed.

Likewise for at least two die-off's of elapids in the last two years as seen in two Melbourne collections. (One of those collections has in fact been cleared of OPMV however).

Transmission of OPMV is according to the literature probably airborne. However for the first time ever, I can report that in the real-world situation of reptile collections this is not so.

All transmission in over a dozen confirmed cases was by fluids, in the form of blood (via mites), water bowls, cleaning cloths or feeding utensils as in forceps.

Airborne transmission did not occur even when affected and unaffected snakes sat within 3 cm of one another and with their cages connected via air-holes in direct line of sight, even though they remained in such a position for weeks. This situation was repeated at least three times in the Hoser collection and has been confirmed and continued in the period following OPMV diagnosis in the collection.

Mites are also vectors for other ailments and must be regarded as the foremost enemy of any reptile keeper.

If other quarantine methods used to stop the spread of OPMV work but a mite plague follows, all defences will be rendered useless even if just one animal is initially affected.

Source of Hoser outbreak

This was traced without much difficulty and in the week from 22 June to end June, numerous other facts of relevance have emerged, including some that contradicted what has been previously reported on OPMV.

What follows is a summary only.

The Hoser infection came from two Floodplain Death Adders (A. cummingi) acquired from Stuart Bigmore on 15 February 2003. The infection of the Hoser collection commenced two months later, after quarantine was dropped for the sole surviving snake. It still carried OPMV. The infection was spread by use of the same forceps to feed snakes rodents. Saliva and fluids left by snakes on the forceps and ingested by other snakes transmitted virus particles.

The Red-bellied Black Snakes sourced from Bob Gleeson in NSW (see above) were also infected from Stuart Bigmore, even though neither man knew each other.

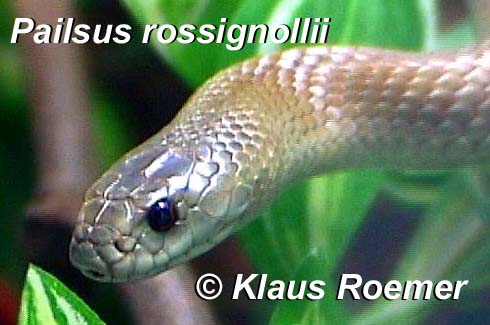

In that case three infected Taipans (Oxyuranus) were passed from Bigmore to Fred Rossignolli (Victoria) on 15 February 2003. Mites transmitted the infection to his entire collection. A number of Tiger Snakes were born at end March 2003 at Rossignolli's facility and were initially uninfected.

This was evidenced by two from the litter removed at birth still being in good health as of end June 2003.

But once the mites attacked the snakes in the weeks following the birth, they too had OPMV and later suffered a mass die off.

In early May, (five weeks later and before the die off commenced) some of the infected Tiger Snakes were sent to Gleeson and via a separate mite infestation, Gleeson's entire collection became infected. Three weeks later, now OPMV infected Red-bellied Black Snakes of Gleeson's were sent to Victoria, where another keeper Scott Eipper had his collection infected.

This represents only part of the chain of infection. The chain down from Bigmore alone totals more than a dozen collections.

Bigmore who works for Ford Motor Company got a job transfer to Japan for 18 months. His snake collection was divided up among several people in February 2003. All got their collections infected.

Until 23 June 2003, no one knew they had OPMV. Until then, all ill health, mass deaths and the like were erroneously attributed by keepers to 'causes unknown' or similar.

Bigmore did not know his snakes had OPMV at the time they left his place.

He therefore could not have advised others of the risks they were taking with his snakes.

Rossignolli's collection did not have OPMV as recently as November 2003. This is known because a female Death Adder (A. antarcticus) loaned to Hoser for two months did not have the infection and did not transfer it to Hoser's collection.

This would have happened as this snake was housed for most of the two months in a single cage with two males.

Noting the wide diversity of sources that Rossignolli acquired his 50-odd snakes from implies that OPMV was either not in Australia or not here until recently. Put another way, if OPMV had been here, Rossignolli should have had it!

Some other sizeable collections in Australia which in theory should have picked up OPMV if it were in circulation and whose quarantine systems (if any!) would not have stopped it, have never had it, or at least so it seems.

All of which points to OPMV being a recent import.

This being so, then if the post-Bigmore infection is not in fact contained, or other snakes sent out by Weigel and unidentified as potential carriers pass on OPMV then OPMV related problems will escalate in the very near future.

Likewise of OPMV is brought into general circulation via other means.

Source of the Bigmore infection

The Bigmore infection can be easily traced.

In October 2002, John Weigel of the Australian Reptile Park (ARP) sent Bigmore a Taipan (Oxyuranus).

It was apparently the source of Bigmore's infection. (The snake is the presumed vector).

Based on the known course of OPMV infections, no other snakes of Bigmore's seem to be likely candidates as the original vector, when reconciled with salient facts such as date received by Bigmore and OPMV in Bigmore's collection.

The ARP die off ran from at least Feb/Mar 2002 to November 2002, which is when Weigel first became aware of the cause of the deaths (OPMV).

Bigmore was never notified by Weigel of these facts or advised in any way that his snake may have been a carrier.

If that advice had been given and received in November (when Weigel became aware of the infection), then Bigmore could have taken appropriate steps and the infection stopped from spreading.

As it happens it wasn't for another three months until snakes were moved from Bigmore's collection.

Weigel's culpable negligence in failing to notify Bigmore has resulted in dozens of deaths and potential infections in more than a dozen collections and many thousands of dollars in losses.

The ultimate cost of this recklessness may take years to manifest.

Bigmore's collection became generally infected via the use of the same cloth to wash water bowls from each cage. Standard disinfectants as used by Bigmore were no barrier to the OPMV.

Notable is that with the possible exception of one affected collection in Sydney (that of Alex Stasweski), not one facility was able to effectively quarantine against OPMV when the infection arrived in an outwardly healthy snake. This is a horrifying statistic!

Source of the ARP Outbreak

The Australian Reptile Park appeared to have kept the OPMV outbreak they had under wraps. The first I heard about it was via an e-mail in January 2003 from Weigel sent to: Mauricio.Perez-Ruiz@nt.gov.au and others. It commenced thus:

Mauricio,

I am surprised that you didn't give me a 'heads up' prior to widely distributing the NSW reports detailing the probable presence of OPMV at the Australian Reptile Park. Your broadcast email was forwarded to me by Peter Mirschin (sic). I have been working with NSW Dept Agriculture on the matter of suspected paramyxovirus in a part of our collection since mid-November, and was told that I would be kept in the loop. May I ask who provided the reports to you? I have tried to contact you on your telephone numbers today, but without success. Please note that the many cc's for my (present) message were lifted from your cc list.

Why Weigel wanted to keep the outbreak under wraps is uncertain, however other parts of the e-mail indicated that the outbreak was now under control and that:

Because we have not been in a position to distribute many snakes since the (2000) fire, we have only had to inform very few collections of the need to use caution re snakes we have supplied.

Based on the Bigmore situation, we know that part of the e-mail to be factually inaccurate.

The urgency of the situation is perhaps better summed up in the report that apparently generated the Weigel e-mail.

That was a report by Bruce, M. Christie, the Chief Veterinary Officer of NSW. It was also posted on the www at: http://www.schlangenforum.de/modules/XForum/viewthread.php?tid=4981 by Viele Grüße Maik on 23 April 2003. It in part read:

The disease has not (officially) been previously reported in Australia.

OPMV causes respiratory disease with wasting and death, and can cause "die-offs" in many species of snakes, including elapids, which includes all Australian venomous snakes.

The statement appears to corroborate evidence to the effect that OPMV is a new and deadly arrival in terms of Australian reptiles.

Now obviously the ARP did not generate the disease in their labs and deliberately unleash it onto the Australian herpetological community, so the logical question then becomes from where did this virus come from?

Weigel's e-mail alleged the infection came from multiple sources based on his 'educated' opinion. This view was later amended (in June 2003) to three likely sources, whom he said all denied any possibility of being the source.

If that is in fact so, then the three keepers probably need to be censured as wholesale denying the possibility of a snake from a large collection being a potential vector of OPMV and without relevant tests is at best conjecture and at worst reckless.

Thus the Weigel e-mails point to OPMV being derived from other Australian collections.

Weigel also points to recent imports of exotic non-native reptiles in anticipation of an amnesty as being the potential original source of OPMV in Australia.

Here he may be close to the mark.

However there is another side to this that is also worth exploring.

The OPMV that has devastated the above collections, including the ARP has essentially targeted elapids and while only moderately adverse to large snakes, is generally deadly to smaller ones and juveniles.

Most exotic snakes brought into Australia have not been elapids and assuming them to be more-or-less immune to OPMV or at least less likely to be carriers than elapids, the most obvious source would probably be an elapid.

Hence my own view that the relatively small number of imported elapids are of greatest interest.

Oddly enough it was the ARP itself that recently acquired some large King Cobras (Ophiophagus hannah), which by virtue of their size would be likely to mask an OPMV infection, but still infect other reptiles.

Suspicion in this direction is added by the fact that the ARP was the first place that OPMV appears to have surfaced (excluding the suspected cases listed above).

Thus it is entirely possible that the ARP itself may have brought in OPMV as shown by the lack of OPMV in collections such as Rossignolli's as late as November 2002, and as a result of the failure to notify Bigmore of the infection, may have in effect foisted this virus into the Australian herpetological community, and perhaps ultimately into the wild here.

My theory (above) in terms of the source of the ARP's OPMV outbreak may be erroneous. But the situation is far too serious to be left in doubt.

All suspected vectors and dead snakes at the ARP can (I assume) be examined, including electron micrographed in order to help ascertain the true source of the infection.

The potential seriousness of OPMV means that such investigation should be done sooner, rather than later … that is if the pathway hasn't been left for too long already to be obscured in total.

KEY POINTS ABOUT OPMV